February – July 2012

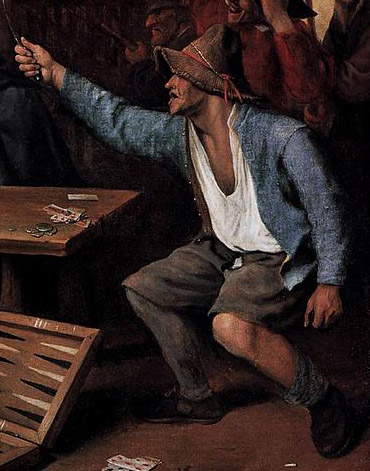

For several years I’ve wanted to make Aaron a 17th Century costume, the cavalier era. But I realized that it would be sensible to make a “practice” version first. That is how this project began. Aaron’s peasant wear is essentially a toned-down version of the same silhouette. It was modeled after two fellows in Molenaer’s 1662 “Peasants Carousing.” This linen outfit consists of doublet and breeches, based on diagram IV in The Cut of Men’s Clothes, and a shirt and bonnet from The Tudor Tailor.

Museum of Fine Arts Boston

I discovered that mid-17th Century working class is as much fun as the more formal styles. Peasants are shown in every imaginable variation of garments: from pants to trunkhose, shirts to long coats. The genre paintings of the Dutch masters provide endless inspiration. I reviewed my entire bookshelf for construction advice, and added to the library. I’ve pared down my writeup to final choices and hopefully interesting details. If only I had sewing mice! I would put them to work immediately on a full 17thC peasant wardrobe.

Patterns:

My plan for the doublet was to use a 16th Century base, then “update” it for the 17th Century by moving some of the style and fitting lines. So I started working on a new and improved doublet pattern in November 2011. I ended up with a nicely fitting 16thC block which will come in very handy. But I could not flat-pattern it into submission. The main difficulty was in straightening out the curved center front. Attempting to do so threw everything so far off that it was easier to start over. Therefore, I consider my “real” start date to be February, when I began with a full scale, enlarged copy of the Diagram IV doublet c. 1630, The Cut of Men’s Clothes.

It was pretty straight forward from there. I just slashed and spread, using the new 16thC doublet block as a guide for size. The pattern obviously needed some peasanty modifications. The shoulder width was reduced and the center front “V” at the waist was made shallower. The tabs are shortened. Each tab overlaps it’s neighbor by about 5/8″ and the tab edges are offset from the doublet seam allowances to avoid bulk. The shape of the sleeves are basically from the original. I think the pattern came together in three muslins. I could have kept going because I’m a big pattern geek, but I was afraid of overfitting. I reminded myself “it’s a peasant costume – it’s okay if it’s not perfect!” Rather than throw caution to the wind, I went ahead and added a side seam with wide seam allowances. (I wasn’t sure whether adding extra width to the side back seam would provide enough flexibility.) Unlike the first doublet I made (the 1560s Florentine), this finished garment can be altered.

Things went much smoother in the land of breeches patterning. Diagram IV was used as a starting point. The pants were made narrower. The legs were left open to copy the Molenaer peasant, though I was hesitant to do this. The majority of full and wide peasant breeches seem to be gathered at the knees. But it’s nice to do something a little unexpected. Wide, open-leg breeches, which were being worn by the upper class at this time, do occasionally crop up in peasant variations. I don’t think I’m misinterpreting paintings such as the Jan Steen below.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, NL

Breeches:

The breeches are in rustic 5.3oz linen from Fabric-store, with pockets and a full muslin lining. They’re pleated to a waistband which is interfaced with hair canvas, using the Couture Sewing method. The placket seen on nearly all the breeches in Cut of Men’s Clothes was added to the front, but it ended up too narrow for machine buttonholes. So I hid some hooks underneath. It seems that there was little concern for gapping flys in this era, so I could have left the whole piece off.

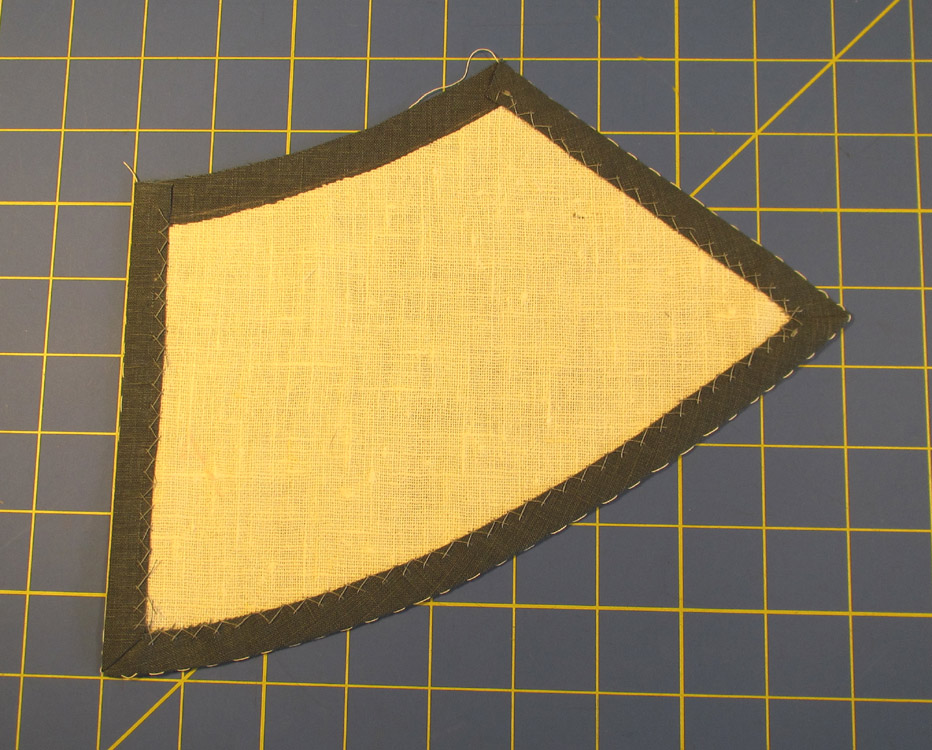

The breeches have two Tudor Tailor pockets. But they were really bulking up the waistline. So I trimmed a couple of triangles from the top of the pockets, in what I thought was a period-appropriate modification. About a month later I found pockets shaped just like this in Patterns of Fashion, p.90. Having never made trunkhose, this detail hadn’t registered on my radar. Still, I decided to pat myself on the back for thinking like a period tailor.

I spent a lot of time mulling over options for holding up the pants. A few portraits have me convinced that peasants had drawstrings as there’s no obvious trussing method and everything is in disarray. Metal hooks were being used in this era for upper class ensembles. (As a side note, I find it most interesting that the placement of the first hook basically corresponds to the placement of an 18thC suspender button. And believe me, I did consider suspenders!) My doublet waist line is cut fashionably above the waist. It’s higher than the pants, which are at waist level. Hooks and eyes, without some additional engineering, won’t work. The eyelet and tie method is completely adjustable. This hook vs. eyelet mystery has given me food for thought. It can possibly be solved with evidence that is in plain sight, but in this case I don’t have to form an opinion. For peasant pants, eyelets are more likely. Surely, those are eyelet holes seen in the Steen. Unwilling to make 10 pairs of eyelets, I used pairs of metal rings, which correspond to pairs of rings on the doublet’s lacing strip. I like the idea that this is completely replaceable.. in case I ever get the urge to make 40 handsewn eyelets. Just for good measure, I made four real eyelets for the closure at center front.

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague

Doublet:

The doublet is in a smooth, tightly woven gray-blue linen from my stash and lined in 3.5 oz linen.

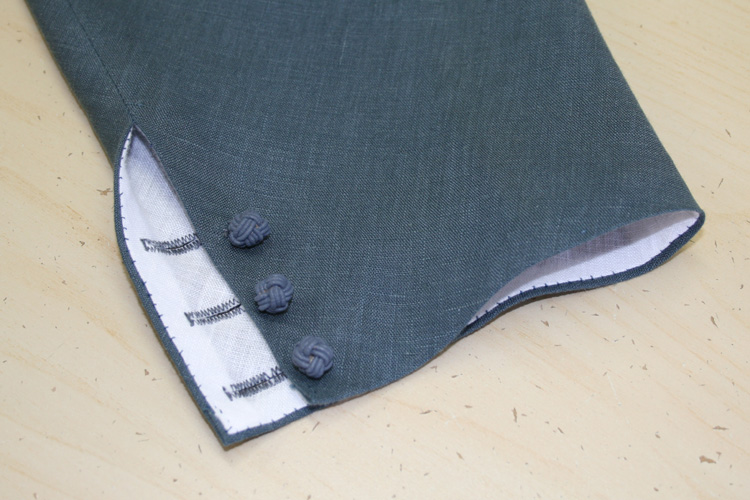

With regard to the doublet’s construction, I relied on The Tudor Tailor and modern tailoring texts. The various tailoring elements are from Patterns of Fashion. Some of the details were included, and others were ignored. It’s a peasant costume, after all. I feel that I have a lot of leeway. Altogether the doublet has six different types of interfacing: muslin (underlining throughout), heavy linen (fronts), medium weight linen (tabs), fusible hair canvas (collar and wings), tricot (cuff buttonhole area), and hair canvas (shoulder piece). My shoulder piece, which is pad-stitched to the linen, is shaped very much like the wool version in the Figure 18 doublet (POF, p.85). Naturally, the doublet shoulders are taped. To simplify construction and keep it peasanty, the belly piece was skipped. The Jan Steen Doublet above, for example, doesn’t seem to have any boning added at the center front. Sometimes it’s debatable: there may be a very short belly piece, or none at all in the Jan Molenaer. You might notice that in the last image the tabs are curling up on themselves, so they’re not heavily stiffened. I wanted my tabs to look more like the inspiration image, the carousing Molenaer peasants. The tab tailoring was an adventure in and of itself.

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Details and Accessories:

Peasant doublets often have very few buttons. My buttons are placed fairly close together. But the variations seen are endless. They’re made of thread-wrapped wire which has been twisted into a ball. They look like the ball half of a frog closure, but they’re hard like buttons and were originally white. A couple of coats of acrylic paint (which my mom mixed to match the doublet), and they’re a decent stand-in for the period buttons (POF, p. 25).

The bonnet is in a linen/cotton blend. It’s lined with petersham and will be adorned with a long feather. It’s a great little hat pattern that I’ve already made three times. But that’s no reason not to have one in each color. Aaron’s also wearing his Renaissance shirt, which is described in more detail on the Renaissance linens page, and I got him some 17thC shoes from Burnley and Trowbridge. When you spend a lot of time on any costume it’s nice to treat yourself to some decent looking shoes.